Breadth of concomitant immune responses prior to patient recovery: a case report of non-severe COVID-19

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-0819-2

Nature Medicine 26, 453–455 (2020)

To the Editor — We report the kinetics of immune responses in relation to clinical and virological features of a patient with mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that required hospitalization. Increased antibody-secreting cells (ASCs), follicular helper T cells (TFH cells), activated CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells and immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies that bound the COVID-19-causing coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 were detected in blood before symptomatic recovery. These immunological changes persisted for at least 7 d following full resolution of symptoms.

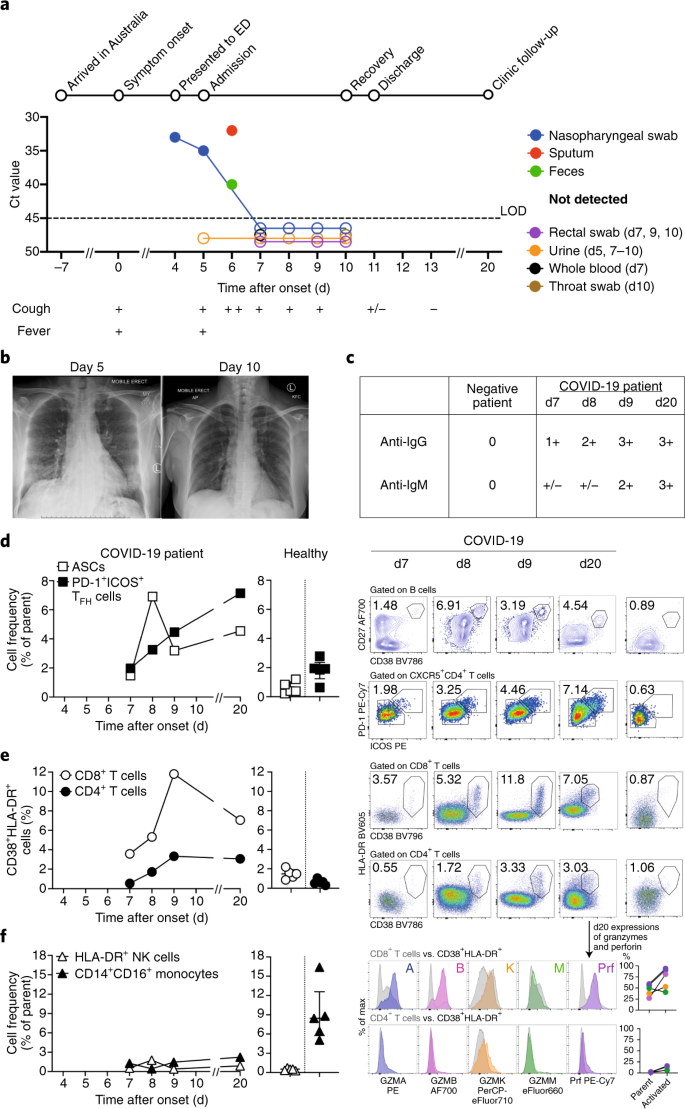

A 47-year-old woman from Wuhan, Hubei province, China, presented to an emergency department in Melbourne, Australia. Her symptoms commenced 4 d earlier with lethargy, sore throat, dry cough, pleuritic chest pain, mild dyspnea and subjective fevers (Fig. 1a). She traveled from Wuhan to Australia 11 d before presentation. She had no contact with the Huanan seafood market or with known COVID-19 cases. She was otherwise healthy and was a non-smoker taking no medications. Clinical examination revealed a temperature of 38.5 °C, a pulse rate of 120 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 140/80 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% while breathing ambient air. Lung auscultation revealed bi-basal rhonchi. At presentation on day 4, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in a nasopharyngeal swab specimen by real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR. SARS-CoV-2 was again detected at days 5–6 in nasopharyngeal, sputum and fecal samples, but was undetectable from day 7 (Fig. 1a). Blood C-reactive protein was elevated at 83.2, with normal counts of lymphocytes (4.3 × 109 cells per liter (range, 4.0 × 109 to 12.0 × 109 cells per liter)) and neutrophils (6.3 × 109 cells per liter (range, 2.0 × 109 to 8.0 × 109 × 109 cells per liter)). No other respiratory pathogens were detected. Her management was intravenous fluid rehydration without supplemental oxygenation. No antibiotics, steroids or antiviral agents were administered. Chest radiography demonstrated bi-basal infiltrates at day 5 that cleared on day 10 (Fig. 1b). She was discharged to home isolation on day 11. Her symptoms resolved completely by day 13, and she remained well at day 20, with progressive increases in plasma SARS-CoV-2-binding IgM and IgG antibodies from day 7 until day 20 (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1). The patient was enrolled through the Sentinel Travelers Research Preparedness Platform for Emerging Infectious Diseases novel coronavirus substudy (SETREP-ID-coV) and provided written informed consent before the study. Patient care and research were conducted in compliance with the Case Report guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. Experiments were performed with ethics approvals HREC/17/MH/53, HREC/15/MonH/64/2016.196 and UoM#1442952.1/#1443389.4.

a, Timeline of COVID-19, showing detection of SARS-CoV-2 in sputum, nasopharyngeal aspirates and feces but not urine, rectal swab or whole blood. SARS-CoV-2 was quantified by rRT-PCR; cycle threshold (Ct) is shown. A higher Ct value means lower viral load. Dashed horizontal line indicates limit of detection (LOD) threshold (Ct = 45). Open circles, undetectable SARS-CoV-2. b, Anteroposterior chest radiographs on days 5 and 10 following symptom onset, showing radiological improvement from hospital admission to discharge. c, Immunofluorescence antibody staining, repeated twice in duplicate, for detection of IgG and IgM bound to SARS-CoV-2-infected Vero cells, assessed with plasma (diluted 1:20) obtained at days 7–9 and 20 following symptom onset. d–f, Frequency (left set of plots) of CD27hiCD38hi ASCs (gated on CD3–CD19+ lymphocytes) and activated ICOS+PD-1+ TFH cells (gated on CD4+CXCR5+ lymphocytes) (d), activated CD38+HLA-DR+ CD8+ or CD4+ T cells (e), and CD14+CD16+ monocytes and activated HLA-DR+ natural killer (NK) cells (gated on CD3–CD14–CD56+ cells) (f), detected by flow cytometry of blood collected at days 7–9 and 20 following symptom onset in the patient and in healthy donors (n = 5; median with interquartile range); gating examples at right. Bottom right histograms and line graphs, staining of granzyme A (GZMA (A)), granzyme B (GZMB (B)), granzyme K (GZMK (K)), granzyme M (GZMM (M)) and perforin (Prf) in parent CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and activated CD38+HLA-DR+ CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Gating and experimental details are in Extended Data Fig. 3.

We analyzed the kinetics and breadth of immune responses associated with clinical resolution of COVID-19. As ASCs are key for the rapid production of antibodies following infection with Ebola virus1,2 and infection with and vaccination against influenza virus2,3, and activated circulating TFH cells (cTFH cells) are concomitantly induced following vaccination against influenza virus3, we defined the frequency of CD3–CD19+CD27hiCD38hi ASC and CD4+CXCR5+ICOS+PD-1+ cTFH cell responses before symptomatic recovery. ASCs appeared in the blood at the time of viral clearance (day 7; 1.48%) and peaked on day 8 (6.91%). The emergence of cTFH cells occurred concurrently in blood at day 7 (1.98%), increasing on day 8 (3.25%) and day 9 (4.46%) (Fig. 1d). The peak of both ASCs and cTFH cells was markedly higher in the patient with COVID-19 than in healthy control participants (0.61% ± 0.40% and 1.83% ± 0.77%, respectively (average ± s.d.); n = 5). Both ASCs and cTFH cells were prominently present during convalescence (day 20) (4.54% and 7.14%, respectively; Fig. 1d). Thus, our study provides evidence on the recruitment of both ASCs and cTFH cells in this patient’s blood while she was still unwell and 3 d before the resolution of symptoms.

Since co-expression of CD38 and HLA-DR is the key phenotype of the activation of CD8+ T cells in response to viral infections, we analyzed co-expression of CD38 and HLA-DR. As per reports for Ebola and influenza1,4, co-expression of CD38 and HLA-DR on CD8+ T cells (assessed as the frequency of CD38+HLA-DR+ CD8+ T cells) rapidly increased in this patient from day 7 (3.57%) to day 8 (5.32%) and day 9 (11.8%), then decreased at day 20 (7.05%) (Fig. 1e). Furthermore, the frequency of CD38+HLA-DR+ CD8+ T cells was much higher in this patient than in healthy individuals (1.47% ± 0.50%; n = 5). CD38+HLA-DR+ T cells were also recently documented in a patient with COVID-19 at one time point5. Similarly, co-expression of CD38 and HLA-DR on CD4+ T cells (assessed as the frequency of CD38+HLA-DR+ CD4+ T cells) increased between day 7 (0.55%) and day 9 (3.33%) in this patient, relative to that of healthy donors (0.63% ± 0.28%; n = 5), although at lower levels than that of CD8+ T cells. CD38+HLA-DR+ T cells, especially CD8+ T cells, produced larger amounts of granzymes A and B and perforin (~34–54% higher) than did their parent cells (CD8+ or CD4+ populations; Fig. 1e). Thus, the emergence and rapid increase in activated CD38+HLA-DR+ T cells, especially CD8+ T cells, at days 7–9 preceded the resolution of symptoms. Details on data reproducibility are in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Analysis of CD16+CD14+ monocytes, which are related to immunopathology, showed lower frequencies of CD16+CD14+ monocytes in the blood of this patient at days 7, 8 and 9 (1.29%, 0.43% and 1.47%, respectively) than in that of healthy control donors (9.03% ± 4.39%; n = 5) (Fig. 1f), possibly indicative of the efflux of CD16+CD14+ monocytes from the blood to the site of infection. No differences in activated HLA-DR+CD3–CD56+ natural killer cells were found.

As pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are predictive of severe clinical outcomes for influenza6, we quantified 17 pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in plasma. We found low levels of the chemokine MCP-1 (CCL2) in the patient’s plasma (Extended Data Fig. 2a), although this was comparable to results obtained for healthy donors (22.15 ± 13.81; n = 5), patients infected with influenza A virus or influenza B, assessed at days 7–9 (33.85 ± 30.12; n = 5), and a patient infected with the human coronavirus HCoV-229e (40.56). Thus, in contrast to severe avian H7N9 disease, which had elevated cytokines IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, MIP-1β and IFN-γ6, minimal pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were found in this patient with COVID-19, even while she was symptomatic at days 7–9.

As the single-nucleotide polymorphism rs12252-C/C in the gene IFITM3 (which encodes interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3) is linked to severe influenza6,7, we analyzed IFITM3-rs12252 in the patient with COVID-19 and found the ‘risk’ IFITM3-rs12252-C/C variant (Extended Data Fig. 2b). As the prevalence of IFITM3-rs12252-C/C in the Chinese population is 26.5% (the 1000 Genomes Project)6, further investigation of the IFITM3-rs12252-C/C allele in larger cohorts of people with COVID-19 is worth pursuing.

Collectively, our study provides novel contributions to the understanding of the breadth and kinetics of immune responses during a non-severe case of COVID-19. This patient did not experience complications of respiratory failure or acute respiratory distress syndrome, did not require supplemental oxygenation, and was discharged within a week of hospitalization, consistent with non-severe but symptomatic disease. We have provided evidence on the recruitment of immune cell populations (ASCs, TFH cells and activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells), together with IgM and IgG SARS-CoV-2-binding antibodies, in the patient’s blood before the resolution of symptoms. We propose that these immune parameters should be characterized in larger cohorts of people with COVID-19 with different disease severities to determine whether they could be used to predict disease outcome and evaluate new interventions that might minimize severity and/or to inform protective vaccine candidates. Furthermore, our study indicates that robust multi-factorial immune responses can be elicited to the newly emerged virus SARS-CoV-2 and, similar to the avian H7N9 disease8, early adaptive immune responses might correlate with better clinical outcomes.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The source data underlying Fig. 1a,c–f and Extended Data Fig. 2 are provided as Source Data. Raw FACS data are shown in the manuscript. FACS source files are available from the authors upon request.

References

-

McElroy, A. K. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 4719–4724 (2015).

-

Ellebedy, A. H. et al. Nat. Immunol. 17, 1226–1234 (2016).

-

Koutsakos, M. et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaan8405 (2018).

-

Wang, Z. et al. Nat. Commun. 9, 824 (2018).

-

Xu, Z. et al. Lancet Respir. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X (2020).

-

Wang, Z. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 769–774 (2014).

-

Everitt, A. R. et al. Nature 484, 519–523 (2012).

-

Wang, Z. et al. Nat. Commun. 6, 6833 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Simmons and all SETREP-ID investigators for their support; Australian Partnership for Preparedness Research for Infectious Disease Emergencies for funding; and L. Rowntree for technical assistance. This work was funded by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (1173871; K.K.). C.E.S. was supported by a Marie Sk?odowska-Curie Fellowship (792532); K.K. was supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1102792); S.R.L. was supported by an NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship and an NHMRC Program Grant; S.Y.C.T. was supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1145033); and X.J. was supported by a China Scholarship Council-UoM Scholarship. We acknowledge public health partners; the major funder of Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory, the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services; and staff involved in patient care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors formulated ideas, designed the study and experiments and reviewed the manuscript; T.H.O.N., M.K., J.D., L.C., C.E.S., X.J. and S.N. performed experiments; T.H.O.N., M.K., J.D., L.C. and S.N. analyzed experimental data; and I.T., T.H.O.N., B.C., S.Y.C.T., S.R.L. and K.K. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.R.L.’s institution received funding for investigator-initiated grants from Gilead Sciences, Merck, Viiv Healthcare and Leidos; and honoraria for advisory boards and educational activities (Gilead Sciences, Merck, Viiv Healthcare and Abbvie).

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Detection of IgG and IgM antibodies in SARS-CoV-2-infected Vero cells.

Immunofluorescence antibody staining for the detection of IgG and IgM bound to SARS-CoV-2-infected vero cells using plasma (diluted 1:20) collected at d7-9 and d20 following onset of symptoms. Immunofluorescence antibody tests for the detection of IgG and IgM were performed using SARS-CoV-2-infected vero cells washed with PBS and methanol/acetone fixed onto glass slides. SARS-CoV-2 was isolated from another COVID patient, and infectivity at cell harvest was ~80%. 10μL of a 1/20 dilution of patient plasma in PBS from days 7, 8, 9 and 20 were incubated on separate wells for 30 mins at 37°C, then washed in PBS and further incubated with 10μL of FITC-conjugated goat anti-human IgG and IgM (Euroimmun, L?beck, Germany) before viewing on a EUROStar III Plus fluorescent microscope (Euroimmun). Prior to detection of IgM antibodies, samples were pre-treated with RF-SorboTech (Alere, R?sselsheim, Germany) to remove IgG antibodies and rheumatoid factors, which may cause false-negative and false-positive IgM results, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and IFITM3-rs12252 in a patient with COVID-19.

(a) Plasma levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in COVID-19 patient at d7-9, healthy individuals (n=5, mean±SEM), patient with HCoV-229e and influenza-infected patients (n=5). Patient’s plasma was diluted 1:4 before measuring cytokine levels (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-17A, IL-1β, IFN-α, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MCP-1, CD178/FasL, granzyme B, RANTES, TNF, IFN-γ) using the Human CBA Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA). For RANTES, sera/plasma was also diluted to 1:50. Healthy donors D6-D10 were of a mean age of 32 (range 22-55 years; 40% females). (b) ‘risk’ IFITM3-rs12252 genotyping for the COVID-19 patient. PCR was performed on genomic DNA extracted from patient’s granulocytes (using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, QIAGEN) to amplify the exon 1 rs12252 region using forward (5′-GGAAACTGTTGAGAAACCGAA-3′) and reverse (5′-CATACGCACCTTCACGGAGT-3′) primers.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Flow cytometry gating strategy for immune cell subsets.

Gating panels are shown for (a) CD27hiCD38hi ASCs and activated ICOS+PD1+ Tfh cells; (b) activated CD38+HLA-DR+ CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells, activated HLA-DR+ NK cells and CD14+CD16+ monocytes; and (c) granzymes (GZM) A/B/K/M and perforin expression on CD8+/CD4+ T-cells and activated CD38+HLA-DR+ CD8+/CD4+ T-cells. Fresh whole blood (200μl per stain) was used to measure CD4+CXCR5+ICOS+PD1+ follicular T cells (Tfh) and CD3-CD19+CD27hiCD38hi antibody-secreting B cell (ASC; plasmablast) populations as described3 as well as activated HLA-DR+CD38+CD8+ and HLA-DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells, inflammatory CD14+CD16+ and conventional CD14+ monocytes, activated HLA-DR+CD3-CD56+ NK cells. After the whole blood was stained for 20 mins at room temperature (RT) in the dark, samples were lysed with BD FACS Lysing solution, washed and fixed with 1% PFA. Granzymes/perforin staining (patient d20) was performed using the eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set after the lysis step. All the samples were acquired on a LSRII Fortessa (BD). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo v10 software. Healthy donors D1-D5 were of a mean age of 35 (range 24-42 years, 40% females).

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thevarajan, I., Nguyen, T.H.O., Koutsakos, M. et al. Breadth of concomitant immune responses prior to patient recovery: a case report of non-severe COVID-19. Nat Med 26, 453–455 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0819-2

-

Published

-

Issue Date

-

DOIhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0819-2

This article is cited by

-

Saving millions of lives but some resources squandered: emerging lessons from health research system pandemic achievements and challenges

Health Research Policy and Systems (2022)

-

Shared mechanisms and crosstalk of COVID-19 and osteoporosis via vitamin D

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Structural assessment of HLA-A2-restricted SARS-CoV-2 spike epitopes recognized by public and private T-cell receptors

Nature Communications (2022)

-

PD-1 blockade unblocks immune responses to vaccination

Nature Immunology (2022)

-

Impact of Chronic HIV Infection on SARS-CoV-2 Infection, COVID-19 Disease and Vaccines